A Pirate Botanist Helped Bring Hot Chocolate to England

William Hughes was a buccaneer with an early recipe for “the American Nectar.”

If you had met him the year his famous book was published, you might have mistaken William Hughes for a mild-mannered gardener. By that time, he had settled into his role at the country estate of the Viscountess Conway, a noblewoman and philosopher, and had published a book on grapevines. But the old man was more than a tottering plant enthusiast. When his treatise on New World botany, The American Physitian, dropped in 1672, its contents revealed a swashbuckling history.

“He was a pirate chocolatier,” says Marissa Nicosia, Assistant Professor of Renaissance Literature at Penn State Abington and co-founder of the Cooking in the Archives blog. Nicosia recently recreated Hughes’s hot chocolate recipe for the Folger Shakespeare Library’s “First Chefs” exhibition, a celebration of the first American culinary celebrities and the indigenous and African people who shaped American cooking.

William Hughes had not intended to become a chocolate celebrity. When the Englishman, who was a botanist by inclination, set out for the New World sometime in the 1630s or ‘40s, it’s possible he had never heard of cacao at all. “Britain was late to the game in terms of exploiting the resources in the Americas,” says Amanda Herbert, an Assistant Director at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Hughes’s botanical studies, and his piracy, were a game of catch-up with the Spanish. His treatise on American botany, one of the first eyewitness English-language accounts of cacao planting and production, alerted the English of the New World resources they had yet to exploit. His notes on hot chocolate preparation, gleaned from encounters with indigenous, colonial European, and African Americans, helped bring the intoxicating brew, once regarded with wariness, to the tastebuds and imaginations of England’s upper classes.

But first, Hughes took to the high seas. He writes that he served on “his majesty’s ship of war,” a polite reference to privateering. At the time, English ships often had charters from the crown entitling them to capture and exploit ships from other countries, a kind of state-sanctioned piracy. Hughes’s ship privateered its way around the Caribbean, from Jamaica and Hispaniola to Florida. As a low-ranking sailor, Hughes was often stuck with the dangerous and tedious job of venturing out in a longboat to explore unknown coasts. But that gave him plenty of time to work on his passion project.

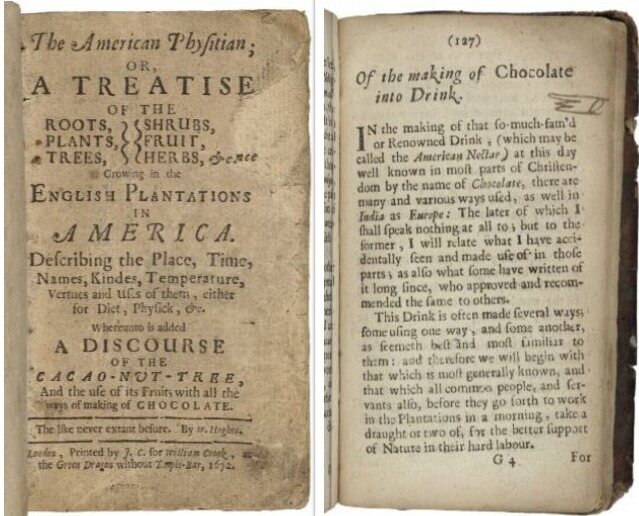

Hughes published his famous A treatise on American botany in 1672. Cooking in the Archives/Public Domain

Published decades after his return to England, The American Physitian includes notes on sugarcane (“both pleasant and profitable”), lime (“excellent good against the Scurvie”), and prickly pear (“if you suck large quantities of it, it coloureth the urine of a purple color”). But the longest entry of the book is dedicated to cacao, “that Fruit, which is the chiefest-ingredient of the deservedly-esteemed Drink called Chocolate.” This drink was so piquant and tempting, so symbolic of the lush riches of the New World, that Hughes dubbed it “the American nectar.”

While he was one of the first to write about it in English, Hughes wasn’t the first to bring chocolate into the European archive. That honor goes to Christopher Columbus himself, who, on his fourth voyage to the Americas, in 1502, encountered a boatful of indigenous people off the coast of Honduras. Their cargo contained a number of strange pods, which a stymied Columbus could only describe as almonds.

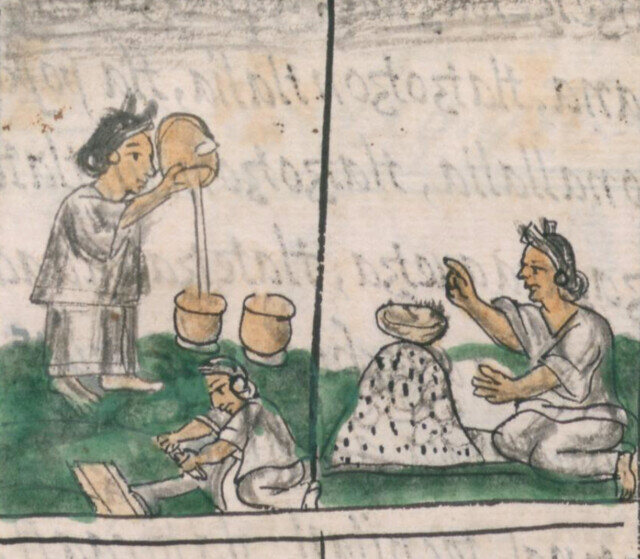

Indigenous Central Americans knew better. They had been consuming chocolate since at least 1400 BC. Pre-Columbian cultural artifacts are full of images and traces of cacao, which they fermented, crushed, and drank with hot water for special occasions. The Codex Zouche-Nuttall, a 14th-century document from the Mixtec people, depicts a couple marrying by sharing a frothing cup of the beverage. Scented with vanilla, honey, and other florals, colored red with annatto, and crowned with a signature crimson foam, cacao embodied life itself. “There was a lot of play around chocolate being like blood,” says Marcy Norton, Associate Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania, who wrote a book on chocolate.

Indigenous Americans also presented cacao to diplomatic guests. It was, perhaps, in this context that Europeans first encountered the drink. In 1518, a group of elite, likely Mayan-speaking Caribbean people presented a Spanish expedition with turkey stew, corn tortillas, and a cacao drink. The Europeans loved the turkey and tortillas, says Norton, but “the cacao drink was very strange to them.”

“Strange” is an understatement. At first, many Europeans simply couldn’t stand chocolate. Benzoni, an Italian traveler in 1500s Nicaragua, said that chocolate was more fit for pigs than humans. A Jesuit traveller in the 1500s compared the foam—one of the most important aspects of the beverage for indigenous Americans—to feces.

By the early 1600s, however, tastes were changing. Maybe it was because Spaniards had spent a century sipping chocolate in diplomatic meetings with indigenous leaders, part of the strategic military alliance that enabled European conquest. Maybe it was the addictive shock of caffeine in the era before coffee and tea captured Europe. Or maybe, as Norton argues, it was a result of the ever-permeable nature of colonial relationships, in which—without intending to, often without wanting to—the colonizer can’t help but take on the tastes and habits of the colonized.

Whatever it was, by the early 1600s, chocolate had seduced Spain. Sold from street carts and chocolate houses favored by missionaries, traders, and others embedded in Transatlantic networks, the frothy beverage enchanted Spaniards as much as its indigenous origins alarmed them. “There’s a lot of satirical and literary production where people are very playful about how taking chocolate makes you an idolator,” says Norton. The fear was real enough to prompt European doctors, priests, and scholars to debate at length how much chocolate was too much, and whether it could be drunk while fasting.

By the time Hughes traveled to the Americas, Spain and the New World were already connected by the habit of hot chocolate drinking, part of a new transatlantic culture forged by trade in sugar, spices, and human beings. Hughes’s description of common hot chocolate ingredients reflects this worldly milieu of traders and the spices they coveted. Variations of the beverage could include “milk, water, grated bread, sugar, maiz, egg, wheat flour, cassava, chili pepper, nutmeg, clove, cinnamon, musk, ambergris, cardamom, orange flower water, citrus peel, citrus and spice oils, achiote, vanilla, fennel, annis, black pepper, ground almonds, almond oil, rum, brandy, sack.”

The bitter undertones of cacao alluded to equally unsettling histories. By the time of Hughes’s voyage, the great pre-Columbian empires had all but fallen. Hundreds of thousands of Native Americans had been killed by European guns, forced labor, and disease. Thousands of enslaved Africans were being taken to American plantations to replace them. As a result of this violent, vibrant exchange, a new Mestizo culture was born, indigenous, African, and European all at once. These people in Empire’s margins—enslaved Africans coaxing sugarcane from island soil; Mestiza ladies mixing indigenous knowledge into chocolate for their Spanish employers or husbands—are the real authors of Hughes’s book.

As with many natural historians of the time, says Herbert of the Folger Shakespeare library, Hughes’s work “was an act of information possession.” His botanical buccaneering was a stand-in for the colonial project as a whole. Like all Europeans in the New World, he extracted resources and knowledge from lands and people that were not his to take. Yet this, says Norton, is the great irony of Europeans’ enduring obsession with cocoa. Hughes may have tried to possess American knowledge, but chocolate, and the indigenous traditions that created it, have possessed Europe ever since.

William Hughes’s Hot Chocolate

Adapted by Marissa Nicosia of Cooking in the Archives for the Folger Shakespeare Library’s “First Chefs” exhibition, part of the library’s ongoing “Before ‘Farm to Table’: Early Modern Foodways and Cultures” series.

Ingredients

This recipe makes two cups of hot chocolate mix.

- 1⁄4 cup cocoa nibs

- 3 1⁄2 ounces or 100 grams of a 70% dark chocolate bar, roughly chopped

- 1⁄2 cup cocoa powder

- 1⁄2 cup sugar

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 1⁄4 cup breadcrumbs or grated stale bread (optional for a thicker drink)

- 1⁄2 teaspoon chili flakes (substitute 1⁄2 teaspoon ground cinnamon for a less spicy drink)

- Milk (1 cup of milk to 3 tablespoons of finished mix)

Preparation

Toast the cocoa nibs in a shallow pan until they begin to look glossy and smell extra chocolatey. Combine all ingredients in a food processor, blender, or mortal and pestle. Blitz or grind until ingredients are combined into a loose mix. Heat the milk in a pan on the stove or in a heatproof container in a microwave. Stir in three tablespoons of mix for each cup of heated milk.

Notes

Hughes lists many other ingredients that indigenous Caribbean people as well as Spanish colonizers added to their hot chocolate. Starting with a base of grated cacao, they thickened it with cassava bread, maize flour, eggs, and/or milk, and flavored it with nutmeg, saffron, almond oil, sugar, pepper, cloves, vanilla, fennel seeds, anise seeds, lemon peel, cardamom, orange flower water, rum, brandy, and sherry. Adapt this hot chocolate to your taste by trying these other traditional flavorings.

SOURCE -> https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/who-invented-hot-chocolate