From the cold waters of Puget Sound to the humid jungles of Panama, the Pacific coastline offers a vast range of wind systems, shaped by topography, pressure gradients, and seasonal shifts. Knowing these winds is crucial for safe and efficient passagemaking.

| Puget Sound Convergence Zone | Puget Sound (Seattle to Everett) | Spring–Fall (varies) | Localized wind and rain bands due to split flow around Olympic Mountains. |

The Puget Sound Convergence Zone (PSCZ) is a distinctive and often dramatic weather phenomenon unique to western Washington State, particularly affecting the maritime and coastal areas around Puget Sound. It occurs when moist air masses from the Pacific Ocean split as they encounter the Olympic Mountains. These airflows travel around the mountains—some curving north over the Strait of Juan de Fuca and others south through Grays Harbor—before meeting again in the lee of the range, directly over the Puget Sound region.

This collision of air streams—often carrying different temperatures, pressures, and moisture levels—creates instability, turbulence, and upward motion in the atmosphere. The result is a narrow band of intensified weather, typically aligned east-west from the Kitsap Peninsula across the central and northern Puget Sound toward Everett, and sometimes as far east as the Cascade foothills. This zone can produce sudden changes in conditions, such as localized heavy rain, snow, gusty winds, small hail, or even thunderstorms—while areas just miles away remain dry or calm.

From a mariner’s perspective, the PSCZ can be particularly tricky. A sail through calm waters can quickly turn into a challenging ride with squally winds, confused seas, or reduced visibility. It’s not uncommon for vessels transiting north to encounter strong wind shear, unexpected gusts, and fast-building waves as they pass through the convergence boundary. Mariners navigating in or near the PSCZ should always monitor NOAA marine forecasts, radar, and real-time weather updates, as these micro-systems can develop quickly and without much warning.

In winter, the PSCZ can shift into a snow-producing engine. Under certain synoptic setups, especially during post-frontal cold air outbreaks, the zone focuses narrow bands of snow over specific areas while others remain clear—a challenge for both forecasters and road crews.

Pilots, sailors, and meteorologists alike have long respected the Puget Sound Convergence Zone as a prime example of topographically influenced mesoscale weather. Its presence underscores how local terrain can significantly impact weather patterns even at relatively low elevations.

For mariners and yacht owners, understanding the PSCZ is key to safe coastal cruising in the Pacific Northwest. While it’s not always active, when it is, the convergence zone demands caution, preparation, and a willingness to adjust course or schedule. As always, the call of the sea in these waters is matched by the need for good seamanship and local knowledge.

The Fraser Outflow Winds: Nature’s Icy Breath Through the Salish Sea

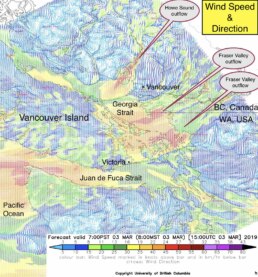

The Fraser Outflow Winds, sometimes referred to as Fraser Outflows or Arctic Outflows, are a defining winter wind pattern that funnels out of mainland British Columbia and into the coastal waters of the Salish Sea, including Boundary Bay, Georgia Strait, and waters around Tsawwassen, Point Roberts, and the Gulf Islands. These winds originate from intense high-pressure systems over the interior and forcefully exit through the Fraser River Valley, where they can reach gale or storm-force levels.

For mariners transiting the Strait of Georgia or entering from the Pacific via the Juan de Fuca Strait, understanding the Fraser Outflow is essential, not only for safety, but also for planning seasonal movements and anchorage choices.

Geographic and Meteorological Overview

The Fraser River Valley acts as a natural wind tunnel. It originates in the Canadian Rockies and carves its way through British Columbia to empty into the Strait of Georgia near Vancouver. In winter, Arctic air masses pool in the Interior Plateau, often generating very strong barometric gradients between the cold high-pressure interior and the comparatively mild, moist marine low-pressure areas off the BC coast.

This pressure difference becomes the driving force behind Fraser Outflows. As the cold, dense air seeks equilibrium, it descends and accelerates westward along the path of least resistance—the Fraser River Valley.

What results is a chilling, powerful wind that can exceed 50 knots in gusts, capable of bringing freezing spray, sub-zero temperatures, and near-whiteout sea smoke conditions along the coast. These winds commonly affect:

• Tsawwassen and Point Roberts

• Boundary Bay

• Howe Sound and English Bay

• The Southern Gulf Islands

• East Vancouver Island, including Nanaimo and Ladysmith

Wind Characteristics

• Seasonality: Fraser Outflows typically occur between November and March, with January and February being peak months.

• Duration: Outflows can last for several days, with rapid onset and slow dissipation depending on how long the inland high pressure holds.

• Temperature Effects: These winds are cold and dry, often lowering the air temperature drastically, particularly at night. Wind chills may plunge well below freezing, even when ambient temperatures hover above zero.

• Wind Strength: Sustained winds in affected areas can reach 25 to 40 knots, with gale- or storm-force gusts. Funnel effects at constricted geographic points like Active Pass or Porlier Pass can increase velocity and turbulence.

• Sea State: Despite originating over land, these winds can create steep, choppy waves in exposed areas of the Strait of Georgia, especially where the outflow meets onshore marine winds.

• Visibility: On cold mornings, these winds can generate sea smoke, a dense fog-like vapor caused when cold air flows over warmer water. Visibility may drop to near zero.

Forecasting Fraser Outflows

Fraser Outflows are well-studied and often predicted by Environment Canada, which issues specific outflow wind warnings in marine forecasts. Indicators include:

• A strong ridge of Arctic high pressure over the BC Interior.

• A deepening Pacific low off the coast or over Vancouver Island.

• A pressure gradient greater than 5 to 10 hPa between Hope, BC (Interior) and Vancouver or Victoria (Coast).

• Rapid cooling inland and high-clear-sky nights.

Modern forecasting tools like Windy, Navionics weather overlay, and GRIB models from OpenCPN with GFS/NAM data will often highlight these conditions days in advance. However, local knowledge remains critical, as the onset can be abrupt and the real-time intensity often surpasses model predictions in narrow valleys and coastal funnels.

Maritime Impact and Navigation Tips

For sailors, yacht captains, and ferry operators in BC’s inner waterways, Fraser Outflows are not just weather events—they are operational hazards.

1. Anchoring and Mooring

• Fraser Outflows are especially hazardous for vessels at anchor in exposed southern reaches of the Gulf Islands and eastern Vancouver Island.

• Anchor holding should be robust, with additional scope and chafe gear, particularly in places like Montague Harbour, Silva Bay, or Ladysmith.

• Marinas on the southeast side of Vancouver Island may offer better shelter than open anchorages.

2. Timing of Transits

• Avoid transiting areas like Boundary Pass or Porlier Pass during the peak of outflow winds. These narrows can experience violent turbulence, wind-over-current stacking, and poor visibility from sea smoke.

• Favor morning departures before the daily peak heating causes wind acceleration.

3. Freezing Spray Risk

• For smaller vessels, especially those with forward-facing windows or exposed decks, freezing spray can rapidly build ice, adding dangerous top-weight.

• Anti-icing measures and delaying departure are often safer than risking hull icing in moderate seas.

4. Crossing to the US

• Vessels headed to Point Roberts, Bellingham, or the San Juans may face direct headwinds and choppy conditions in Boundary Bay and the southern Gulf Islands. Mariners crossing the border should ensure they have alternate ports in mind.

5. Fuel and Engine Notes

• The dry, dense air increases engine efficiency, but may exacerbate problems with fuel waxing if diesel is untreated.

• Consider antigel additives and monitor your fuel temperature, especially for vessels that carry summer-blend diesel into a BC winter.

Real-World Incidents and Cases

Over the years, Fraser Outflows have contributed to:

• Dragging anchor events in Silva Bay and Newcastle Island.

• Sinking of smaller boats in gust fronts near Point Grey.

• Ice accretion on vessels transiting toward the Sunshine Coast.

• Ferry service disruptions, notably at Tsawwassen terminal, due to rough docking conditions.

Many a sailor has learned the hard way not to underestimate the wind’s strength at the mouth of the Fraser. One local captain put it plainly: “If you see snow-capped peaks inland and clear skies to the west, double-check your halyards—it might blow harder than you expect.”

Posse Perspective: Strategic Notes for Cruisers

From an Ocean Posse navigation standpoint, knowledge of the Fraser Outflow is particularly useful for:

• Vessels staging northbound or southbound through the Salish Sea.

• Foreign-flagged yachts overwintering in BC or Puget Sound who may not be accustomed to local microclimates.

• Insurance compliance: Understanding these wind events can reduce unnecessary risk exposure during haul-outs, maintenance transits, or off-season delivery passages.

• Fleet coordination: When moving together or during meetups in the Gulf Islands, outflows should be a determining factor in anchorage selection.

Conclusion

The Fraser Outflow Winds are a spectacular but hazardous display of winter’s influence on maritime weather in coastal British Columbia. Born of icy high-pressure systems and funneled through the Fraser River Valley, these winds transform tranquil anchorages into wind tunnels and add a layer of complexity to cruising during the off-season.

For the savvy sailor, however, they are neither mysterious nor unmanageable. With proper forecasting, prudent seamanship, and the fellowship of the fleet, you can navigate Fraser Outflows as part of the grand adventure that is Pacific Northwest sailing.

Fair winds, except when they scream from the east

Santa Ana Winds – The Desert Breath That Meets the Sea

Every coastal sailor from San Diego to Santa Barbara has a Santa Ana story. These winds are not the gentle sea breezes we welcome on a hot afternoon, they are the desert’s breath sweeping downhill, gathering speed through canyons, and rushing out over the Pacific, just as you are trying to get to Mexico

They can give you a fast push offshore or punish an ill-prepared yacht at anchor. Like the tides and currents, they’re part of the rhythm of this coast – and respecting them is as essential as charting your course.

Where They Begin

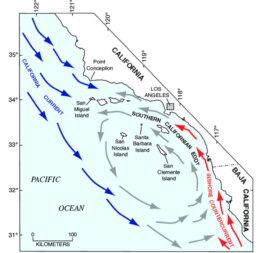

Santa Anas are born inland. When high pressure settles over the Great Basin and low pressure lingers offshore, the gradient pulls air downslope toward the coast. As that air compresses through mountain passes, it warms and accelerates.

By the time it pours out near Los Angeles or San Diego, what began as cool desert air is now hot, dry, and forceful – sometimes steady, sometimes violent. For mariners, it means the wind doesn’t come from the sea, but from the land, reversing the normal pattern and changing the game entirely.

When They Blow

These winds can turn up any month, but the prime season runs September through April, with fall , especially October and November, notorious for the strongest bursts.

A Santa Ana event can last a single night or blow for days. Often the fiercest hours come at 1 AM, you go to sleep with calm seas at anchor and wake up with your rigging howling. By midday, they sometimes ease, but not always.

What to Expect on the Water

Unlike many wind systems, Santa Anas flatten seas near the shoreline. At first glance, it can look like dream sailing , flat water, brisk winds, and a quick reach out of the harbor.

But offshore the story shifts. Pacific swell keeps marching in from the west, and when it collides with strong offshore wind, you get steep, confused chop. The further you press out – toward Catalina, San Nicolas, or beyond, the rougher and more unpredictable it gets. The Chanel Islands are just far enugh of shore that they are in the brunt of this onslaught.

Closer to shore, gusts funnel through canyons. In one cove it may be dead calm, in the next bay a full gale. Sailors who’ve tried to anchor off Malibu or Newport during a Santa Ana have learned how quickly a secure night can turn into a dragging-anchor nightmare

More Than Wind: Fire and Haze

The Santa Anas are infamous on land for fueling wildfires, and at sea the byproduct is smoke. Ash can drift far offshore, coating decks and dimming horizons. In heavy fire years, visibility drops to a few miles, even in mid-day.

In those conditions, VHF radio, radar and AIS become necessities, after all Long Beach commercial traffic is relentless and playing frogger getting across these busy shipping lanes with smoke is hazardous.

Tactics

Check the pressure map:

A strong gradient from the Great Basin to the coast is your early warning. NOAA will issue advisories, but the chart tells the story best.

Reef early, reef deep:

If Santa Anas are in the forecast, set conservative sails before you clear the breakwater. It’s easier to shake a reef out than to claw one in under a surprise gust.

Don’t trust the flat seas near shore:

They lull you into a sense of security. Nine miles offshore, it’s a different ocean.

Anchor with the wind in mind:

Harbors that are snug in a westerly swell may be exposed when the wind howls out of the east. Choose your basin accordingly and double your lines.

Fatigue:

The hot, dry wind gnaws at crew morale. Hydrate, rotate watches, and keep tempers cool even when the wind is not.

Sailor’s Dilemma:

One of the great temptations is to let a Santa Ana carry you south. From Los Angeles to San Diego, the offshore push can feel like magic – just do not try to get back into port !

Santa Ana tales float around every gunkhole

A racing fleet bound for Ensenada scattered by a surprise blow, half the boats towed back in by dawn.

A ketch in Newport Harbor dragging across the anchorage at 3 a.m., clattering into half a dozen boats before the crew could reset.

Yachts heading to Catalina enjoying champagne sailing downwind, only to fight back through chop and gale the following day.

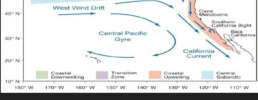

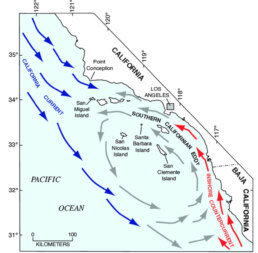

The California Current runs south along the Pacific coast from British Columbia to Baja California. It is a cold current, fed by waters descending from the Aleutians, and is part of the world’s great upwelling systems.

Driven by steady trade winds, surface waters are pushed westward, pulling up colder, nutrient-rich water from below. This upwelling is strongest in summer, especially near 35° and 41°N, and it fuels rich plankton blooms that support thriving fisheries and abundant sea life. Mariners often notice fog, cooler sea surface temperatures, and strong coastal winds during this season.

By late summer, eddies spin off the coast, carrying water offshore. In winter, when upwelling weakens, the Davidson Current sets northward close to shore, bringing warmer water.

Sailors crossing these waters can expect seasonal shifts: cold, nutrient-filled currents in summer that support sea life but bring chillier sailing conditions, and a gentler, warmer countercurrent in winter.

1. The Dominant Winds

• Northeast Trade Winds:

Blow steadily from the northeast to the southwest, especially strong in spring and summer. These winds push surface waters offshore (via the Coriolis effect), which is what triggers the famous coastal upwelling.

• Northwesterlies: Along the California coast, the prevailing surface winds in summer are strong NW winds, especially between Point Conception and Cape Mendocino. These winds can blow at 15–25 knots for days, building steep seas and making southbound passages faster and northbound ones harder.

2. Seasonal Behavior

• Spring and Summer (March–July)

◦ Winds are strongest and most consistent from the northwest.

◦ They accelerate around coastal headlands (Point Conception is notorious).

◦ This is the season of maximum upwelling—cold fog, rough seas, and strong breezes are common.

• Late Summer to Early Fall (August–October)

◦ Winds start to weaken and shift slightly.

◦ Coastal fog remains but less persistent.

◦ Eddies may form near the coast, altering local wind patterns.

• Winter (November–February)

◦ The dominant northwesterlies relax.

◦ Southerly storm winds from the North Pacific move in, tied to passing low-pressure systems.

◦ This is when the Davidson Current flows northward, counter to the California Current. For sailors, this means warmer water and easier northbound passages, though winter storms can be severe.

3. Practical Effects for Mariners

• Summer southbound runs are fast, with strong NW winds pushing you along—but often cold, foggy, and rough.

• Summer northbound runs are a slog, with headwinds and choppy seas; mariners often wait for short weather windows.

• Winter sailing brings more variable winds, sometimes southerly with storms, but calmer between systems. Northbound passages are easier in this season, though storm risk is higher.

The Nortes are strong seasonal winds that affect the Baja California Peninsula, especially during the late fall and winter months (roughly November through March).

What They Are

• Cold, dry winds that blow from the north and northwest, originating from high-pressure systems over the U.S. Great Basin and the deserts of the American Southwest.

• They funnel down through the Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez), accelerating as they pass between mountain ranges.

Where They Hit

• Most pronounced in the northern and central Sea of Cortez (e.g., Bahía de los Ángeles, Santa Rosalía, Mulegé, Loreto).

• Can extend further south but usually weaken past La Paz.

• The Pacific side of Baja is less affected, though northerlies can still bring steep seas offshore.

Strength and Sea Conditions

• Sustained winds of 20-30 knots are common, with stronger gusts.

• They kick up short, steep seas, making passages uncomfortable or dangerous for small craft.

• Often follow a clear, cool air mass and can last several days.

Timing and Pattern

• Typically begin in the afternoon or evening after a frontal system passes to the north.

• Can persist for 2–4 days before easing.

• Between Norte events, conditions may be calm with light southerlies.

For Mariners

• Cruisers often wait for a weather window to avoid being caught in them.

• Sheltered anchorages (like Puerto Escondido or Bahía Concepción) are important refuges.

• Monitoring forecasts (such as from SailFlow, PredictWind, or local VHF nets) is crucial during the season.