New Caledonia to Australia

The passage from New Caledonia to QLD, Australia is a common route for westbound cruisers completing a South Pacific season and heading to Australia for cyclone season. Below is an overview covering route options, timing, weather patterns, entry procedures, and navigational notes.

🧭 General Passage Overview

• Route: Nouméa (New Caledonia) to Bundaberg (Queensland, Australia)

• Distance: ~820 to 900 nautical miles depending on departure and arrival points

• Direction: West-southwest

• Time at sea: 5 to 7 days for most cruising yachts (avg. speed 5-7 knots)

• Destination port of entry: Bundaberg Port Marina (Port of Bundaberg – Biosecurity and Customs clearance available)

⛵ Recommended Timing

• Best Season: Late October to mid-November

• Why: This window is after the South Pacific cruising season and before cyclone risk increases. Weather is more stable and frontal systems in the Coral Sea are less frequent.

• Avoid: December onward due to increasing cyclone activity; also avoid departing during strong SE tradewinds or when a Tasman low is active.

🌦 Weather & Routing Considerations

• Prevailing winds: SE tradewinds (10-25 knots)

• Typical pattern: Start with E-SE winds, often light near New Caledonia and building mid-passage; expect more variable winds approaching the Queensland coast.

• Troughs & Fronts: Watch for cold fronts sweeping up from the Tasman Sea. These can bring strong SW to NW winds and squalls.

• Recommended Routing Tool: Use Weather Routing plugin in OpenCPN or services like PredictWind or FastSeas. GRIB files essential.

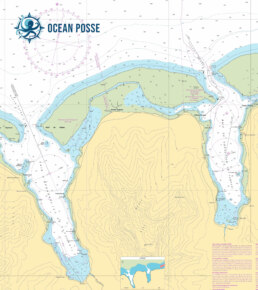

🗺 Navigational Notes

• Departure Point: Nouméa (Port Moselle Marina) or Baie de Prony for a better jump-off

• Arrival Waypoint: Bundaberg Fairway Buoy (then follow river channel to marina)

• Hazards:

◦ Coral Sea can become rough with wind-over-current conditions.

◦ Avoid lingering in the Capricorn Channel in a strong southerly.

◦ Stay alert for commercial shipping lanes and fishing buoys closer to Australia.

🇦🇺 Arrival in Australia – Border Procedures

• Biosecurity: Australian Border Force and Biosecurity (DAFF) require advance notification.

• Notice of Arrival: Must be submitted 96 hours before ETA (Australian Border Force Yacht Arrival Info)

• Prohibited Items: Fresh produce, untreated wood, animal products, seeds, etc.

• First Port of Entry: You must check in at an official port — Bundaberg is one of the most cruiser-friendly with a smooth process and marina support.

⚓ Bundaberg Port

• Coordinates: 24°45.802′ S 152°23.426′ E

• Services:

◦ Biosecurity & customs clearance on-site

◦ Friendly staff accustomed to international arrivals

◦ Fuel, haul-out, chandlery, provisioning

• Nearby town: Bundaberg (short taxi ride) for groceries, banks, travel services

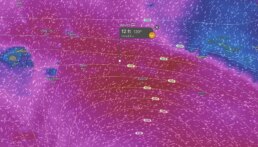

WEATHER FORECAST

Swell

CRUISING ° FLEET UPDATE & NEWS ° 2025-06-29

“The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure.

The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences,

and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon,

for each day to have a new and different sun.”

CRUISING ° FLEET UPDATE & NEWS ⛵ 2025-06-29

-

Pictures Of The Week 📷

-

NW Siciliy 🇮🇹 Italy – Golfo Di Castella to San Vito Lo Capo

-

Midnight Sun 🇳🇴 Voyage from Oslo to Bergen

-

Central South Pacific

da’ F^&*~’g MIDDLE

-

Marina De Cascais

Portugal

-

Rare Earth

Minamitorishima Island

-

Heiva’i Tahiti 2025

FRENCH POLYNESIA

-

Ocean Posse BBQ 🇵🇫 in Tahiti

-

Rogue Waves 🌊

-

SY Galatea ⛵ Ocean Posse Yacht For Sale in Panama

-

Bora 🌬️ Wind

-

Must See 🇲🇽 Sierra De San Francisco Sea Of Cortez

-

Meet the Fleet – SY KNOT RIGHT & MV EPIC

-

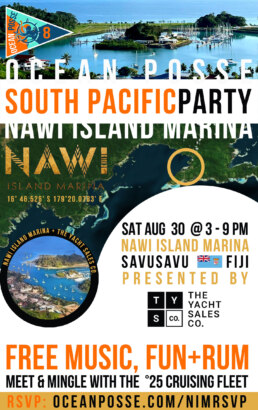

Rum & Kava Fiji 🇫🇯 Nawi Island Marina brought to you by the Yacht Sales Co.

-

Noumea Yacht Services

New Caledonia

-

💬 Tidbits

-

Dock Party 🎉 Red Frog Marina

-

Petty Thefts 🥷 Bocas del Toro

-

Ocean Posse info strikes again – where is Zuckerberg’s Yacht ?

-

PICTURES OF THE WEEK

Perception at anchor near Lady Liberty yesterday.

SY PERCEPTION

Becalmed waters and Nice motoring conditions around Cape Hatteras:

As we pass over about 15 shipwrecks in the area.

Above header image – red skies and a Little color on our ride up to Chesapeake Bay.

MY KOSMOS

Becalmed waters and Nice motoring conditions around Cape Hatteras:

( header image – red skies and a Little color on our ride up to Chesapeake Bay.)

SY KALIYAH

Late sunset over Red Frog Marina yesterday. Starlink’s back! 🙂

SY SERENITY

check their blog here https://www.sailblogs.com/member/pacificnomads/

SY ILIOHALE

Allan & Rina – Lagoon 45′

Allan & Rina – Lagoon 45′

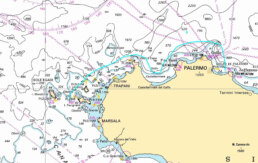

NW Siciliy 🇮🇹 Italy Golfo Di Castella to San Vito Lo Capo

Pictures along the way from Mondello, Golfo di Castella and now San Vito lo Capo. North West Coast of Sicily Italy . This place has white sand beach, and I can’t wait to get my feet in it!

SY SMALL WORLD III

Midnight Sun 🇳🇴 VOYAGE FROM Oslo to Bergen

Lucky Chucky and LIsa on their epic voyage up the cost of Norway

MY HO’OKIPA 🇺🇸 Lucky Chukcy & Lisa –Selene 43′

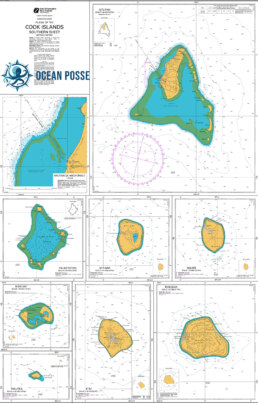

CENTRAL SOUTH PACIFIC 🌐 F^&*~’g MIDDLE🇨🇰 COOK ISLANDS

THE DANGEROUS MIDDLE

Between French Polynesia and Tonga/Fiji lies a notorious stretch of open ocean often called The Dangerous Middle. Unlike the well-defined tradewind routes to the east, this part of the South Pacific is unpredictable, uncomfortable, and occasionally unforgiving. Here’s what makes it challenging:

1. Weather Systems & Pacific Lows

-

Unstable Trade Winds: The reliable SE trades start breaking down in this zone. Expect calms, unexpected shifts, and squalls.

-

Frequent Lows: Every 6-7 days, mid-latitude lows brew in the Tasman Sea and sweep east toward Chile. When they arc north into this area, they can bring gale-force winds, heavy rain, and messy seas.

-

SPCZ Hazards: The South Pacific Convergence Zone is often in play, shifting north or south unpredictably. It’s a factory for squalls, thick cloud, and wind instability—hard to avoid and harder to forecast.

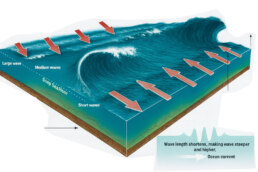

2. Swell Conflicts & Sea State

-

Southern Ocean Swells: Long-period swells from deep south storms frequently reach this area, often crossing the direction of prevailing wind waves.

-

Confused Seas: The clash of south swells and east wind waves creates short-period, choppy conditions that can wear down crew and gear. Forecast models often fail to show the true state of the sea.

3. Route Planning & Strategy

-

Timing Is Everything: May to October offers the most stable trades and the fewest lows pushing north.

-

Weather Routing Required: This is not a set-it-and-forget-it passage. Real-time updates, weather routers, or tools like Starlink and PredictWind can help you dodge the worst.

-

Latitude Choice: Some head north near the equator to avoid the SPCZ, others drop south around 20°S for more consistent trades. Either way, flexibility is key – and plenty of diesel to motor through the calms.

Seafarers can be challenged by this leg of a Pacific crossing but with timing, it’s manageable. Most choose to break it up with stops in places like Suwarrow (Cook Islands) as you enter from the north pass it is doable in most conditions.

Aututaki, Beverage Reef or Niue, require good weather windows. You have 300 – 600 nm legs to do between each low passes you on the bottom – the further north you voyage the more settled the wave and conditions will be.

Beneath The Dangerous Middle runs a weekly a conveyor belt of powerful low-pressure systems

It moves from the west to east across the Southern Ocean. These lows form primarily in the Tasman Sea and roll out under New Zealand every 6 to 7 days, heading toward Chile. Their path may seem distant on the chart, but the long-period swell trains they produce don’t respect boundaries and even creates treacherous conditions for the bar entries in El Salvador.

( See KNOT RIGHT’S image in meet the the fleet)

• Southern Ocean Storm Tracks: These lows generate gale force winds over vast fetches, pushing up deep, energy-rich swells. Even if the center of the low stays far far south in the 40-and 50’s , the swell propagates thousands of miles northward into the tropical South Pacific – and all the way to provide surf in Cost Rica and Panama.

• Arrival in the Middle: By the time these swells reach the region between French Polynesia and Fiji/Tonga, they’re typically 2–4 meters and still packing long periods – 12 to 20 seconds isn’t uncommon. When they meet opposing wind waves from easterly trades or squalls from the SPCZ, the sea state becomes disorganized and steep.

• Confused Cross-Seas: Add a second swell from another direction, and you’ve got a 3-way sea: trade chop, south swell, and remnants of a prior system. Not dangerous in isolation—but relentless in motion, tiring for crew, and hard on autopilots and rigging.

• Routing Tip: GRIB files show wind and pressure, but not always the full picture of cross-swells. Use swell overlays and regional models (e.g. FNMOC or WW3) to spot these long-period pulses before they arrive.

MARINA DE CASCAIS  PORTUGAL

PORTUGAL

SPONSORS THE OCEAN POSSE

38° 41.5466′ N 009° 24.935′ W

Marina Cascais has been the setting for some of the most important sailing events in the world.

We are proud to offer a special 15 % discount to all the Ocean Posse recipients.

Reservations must be made with advance so that we can check availability with time.

CONTACT

Marina de Cascais

Casa de S. Bernardo, 2750-800 Cascais

T (+351) 214 824 800

E info@marinacascais.pt

E reception@marinacascais.pt

Reception Hours Winter 9:00 – 18:00

Reception Hours Summer 08:30 – 20:00

T (+351) 214 824 800

F (+351) 214 824 860

SERVICES

- Fuel Dock

- Restaurants

- Catering

- Automatic Laundry Facilities

- Showers

- Heliport

- Wifi

- Mail & Receiving of correspondence

- 70 Ton Gantry Crane

- 2 Ton Crane

- Ramp

- Hull cleaning

- Trailers

- Jet ski package

- Dry docking

NEARBY MUST SEE

1. Boca do Inferno (Hell’s Mouth)

A dramatic seaside cliff formation where waves crash into a natural chasm. Spectacular in rough weather, it’s a favorite for photographers and sea-watchers.

2. Santa Marta Lighthouse & Museum

Just steps from the marina, this 19th-century lighthouse now includes a museum with maritime exhibits and stunning views from the tower.

3. Cascais Citadel (Cidadela de Cascais)

A historic fortress overlooking the marina, now home to an art center, restaurants, and a boutique hotel. Great for a sunset walk.

4. Palácio da Cidadela

Located within the citadel, this former royal summer residence is now a museum showcasing Portugal’s regal past.

5. Condes de Castro Guimarães Museum

A fairytale-style palace by the sea, filled with antiques, artwork, and a rich library. The surrounding gardens are perfect for a quiet stroll.

6. Casa de Santa Maria

A charming early 20th-century villa with tilework and period interiors. Guided tours give insight into Cascais’ aristocratic era.

7. Cascais Beaches: Praia da Rainha, Ribeira, Duquesa & Conceição

These small, sandy beaches are steps from the marina and ideal for a swim, SUP, or just sunning with a view of anchored yachts.

8. Seafront Promenade to Estoril (Paredão)

A beautiful 3 km coastal path perfect for walking or biking past beaches, tidepools, and cafés all the way to Estoril.

9. Guincho Beach & Cabo Raso

About 10 km west, this wilder coastline is famous for windsurfing, kitesurfing, and dramatic Atlantic views. Great by e-bike or rental car.

10. Poço Velho Prehistoric Caves

A lesser-known archaeological site right in town, offering a glimpse into Cascais’ ancient past through guided visits of the burial caves.

ON THE SUBJECT OF RARE 💎 MATERIALS

Minamitorishima Island 🇯🇵 Japan

24° 16.9360′ N 153° 58.6173′ E

Minamitorishima or Marcus Island is a tiny, triangular coral atoll belonging to Japan- the easternmost point of the country- located in the northwestern Pacific about 1000 nm southeast of Tokyo

🗺️ Geography & Strategic Status

• Shape & Size: Roughly equilateral triangle, covering 370 acres with a 3.5 nm coastline. It lies directly on the Pacific Plate beyond the Japan Trench

• Elevation & Reef: Flat, sitting 5–9 m above sea level with a sunken central depression. Surrounded by fringe reefs and deep contrast waters plunging ~1,000 m below

Under Japan’s jurisdiction, it anchors a massive exclusive economic zone

.

🏛️ History & Human Use

• Early Sightings: First recorded by a Spanish captain in 1543, sighted again in 1864 by a Hawaiian missionary ship, and marked by American and French surveyors later in the 19th century

• WWII: Militarized by Japan, bombed during 1942–43, and surrendered in 1945 after U.S. naval attacks

• Post-war Control: Handed to U.S. in 1952, returned to Japan in 1968. Hosted U.S. Coast Guard LORAN‑C station (1964–93), now supports Japanese meteorological, JSDF, and coast guard operations

🚀 Modern Significance

• Access: No civilian access; staffed by Japan Meteorological Agency, Self-Defense Forces, and Coast Guard on rotations

• Research: Recent seabed surveys revealed rich polymetallic nodules in the EEZ- containing nickel, cobalt, copper- attracting deep‑sea mining interest

A 2018 study (University of Tokyo and JAMSTEC) revealed extremely high concentrations of rare earth elements in deep-sea mud about 6,000 meters below the ocean surface near Minamitorishima.

Over 16 million tons of rare earth oxides.

Enough to supply global demand for yttrium, europium, terbium, and dysprosium for hundreds of years.

🧭 Why It Matters:

These rare earth elements (REEs) are crucial for:

High-efficiency magnets (used in electric vehicles and wind turbines)

Smartphones, electronics, optics, lasers

Defense systems (missile guidance, sonar)

🌐 Strategic Implications

China controls ~90% of the world’s REE supply chain. Japan seeks to reduce dependency by tapping its own resources- Minamitorishima is key to that.

• The island’s EEZ (430,000+ km²) gives Japan exclusive rights to explore and extract.

Heiva i Tahiti 2025 🎉 FRENCH POLYNESIA

🎭 Heiva i Tahiti – Competitions & Cultural Interpretations

🔥 Dance Competitions (‘Ori Tahiti)

Main Divisions:

-

Hura Tau: Professional dance troupes, often over 100 dancers, delivering powerful performances with elaborate staging and intense choreography.

-

Hura Ava Tau: Amateur ensembles focused on grace, storytelling, and traditional themes, though still highly polished.

Core Dance Styles:

-

‘Ōte’a: High-energy group dance featuring rapid hip movements and synchronized percussion. Themes often depict war, navigation, harvest, or nature.

-

Aparima: Slower, graceful dance emphasizing hand gestures that narrate love stories or myths—comparable in tone to hula.

-

‘Ahupūrotu: Characterized by detailed, layered costumes and elegant movement. Often used to convey deeper, ceremonial messages.

-

Hivinau: A circular formation dance performed around musicians. Typically used to open or close a performance, referencing community unity and the sea.

Performance Flow:

Each troupe develops a full-length narrative expressed through movement, percussion, costume, and chant. Judging focuses on creativity, authenticity, expression, and cohesion across music, costume, choreography, and staging.

🥏 Traditional Sports

Often dubbed the “Polynesian Olympics,” Heiva’s sports segment—called Heiva Tu’aro Mā’ohi—features:

• Stone-lifting

• Javelin throwing

• Ou-trigger canoe (va’a) races around Pointe Venus and Papeete waters

• Coconut climbing and cracking

• Horse racing, spear throwing, fire-walking, fruit-lifting contests

🎙️ Interpretation & Cultural Resonance

• Heiva derives from hei (“assemble”) and va (“community”), making it a “celebration of life” and cultural unity

• Performances weave together ancient Polynesian values, legends, language, and heritage—ostensibly ritualistic, yet fiercely modern and evolving

• Groups and soloists undergo months of intense rehearsal (thousands of hours each year), reflecting both discipline and devotion .

• While debate exists about tourism’s influence, many Tahitians see Heiva as a vital vessel for preserving and celebrating living traditions

OCEAN POSSE BBQ MEET UP 🔥

MARINA TAHINA 🇵🇫 TAHITI

SAT JUL 12 15:00 – 18:00

Captain Alan of SY Cyrolia and Marina Tahina are hosting an impromptu BBQ this Sunday at Marina Tahina. 🧭 Bring Your finest grill-worthy protein anda side dish or treat to share with the fleet

🍹 Free Rum will be provided for all

SY CYROLIA

Rogue Waves 🌊 AN Overview

1. What Is a Rogue Wave?

A rogue wave is an unusually large and unexpected ocean wave that is more than twice the height of the surrounding waves. These waves appear suddenly and in extreme cases have reached heights exceeding 25 meters, posing risks to even larger ships and offshore structures.

2. How Rogue Waves Form

a) Constructive Interference

When several smaller waves traveling at different speeds and directions intersect, their crests can align, temporarily forming one much larger wave. This phenomenon is random and not sustained, but it explains many rogue wave events.

b) Nonlinear Focusing

In certain sea conditions, wave energy can be transferred between waves in a way that one wave becomes sharply amplified. This is described by nonlinear wave theories that show how energy can become concentrated in a single, massive crest.

c) Wind Amplification

Strong and persistent winds can add energy to existing waves, boosting their size. When wind and wave direction align for long distances (fetch), significant wave height increases, creating conditions ripe for rogue wave formation.

d) Current Focusing

Rogue waves are more likely in areas where waves meet strong opposing currents. The interaction causes the waves to slow down and steepen, compressing their wavelengths and increasing their height. This is commonly observed in places like the Agulhas Current off South Africa.

3. How Rare Are They?

Rogue waves were once thought to be maritime myths, but they are now recognized as real and surprisingly frequent. Modern satellite and buoy data show they can occur more often than previously assumed. Notable examples include a 25.6-meter wave off Norway and a 17.6-meter wave recorded off the coast of British Columbia.

4. Why They Matter

Rogue waves are extremely powerful and unpredictable. Their steep walls and deep troughs exert immense force on structures, often exceeding what vessels are designed to withstand. Ships may encounter such waves without warning, and offshore platforms must be engineered to handle the potential impact.

5. Can We Predict Them?

While full prediction remains a challenge, progress is being made. Advances in satellite imaging, wave modeling, and artificial intelligence are helping scientists identify ocean regions with elevated rogue wave risk. Key factors being monitored include:

• Areas with strong, opposing currents

• Rapid weather changes

• Convergence zones and long wave fetches

OCEAN POSSE YACHT FOR SALE 🇵🇦 PANAMA

SY 🇺🇸 GALATEA – 1982 MorgaN 462 KETCH

$114,500 Fully Loaded

Offered for sale is a beautifully upgraded NEW PRICE FOR A SUMMER SALE and currently cruising, this Morgan 462, a center-cockpit, world-capable cruiser renowned for her strength, comfort, and versatility, is waiting for you to sea trial.

Step aboard the lovely refit yacht with its perfect blend of classic design and modern upgrades. Designed by Charley Morgan and built for serious offshore cruising, this center cockpit cutter rigged ketch is known for her robust construction, spacious interior and impressive passage making capabilities.

This yacht has undergone extensive refits and modernization, making her an exceptional choice for bluewater sailing or liveaboard life. Her two cabin design with port side extra settee make a comfortable boat for a family or a couple.

Click here for details >>

OCEAN POSSE PARTNERSHIP MARINAS

🇦🇺 AUSTRALIA

🇧🇸 BAHAMAS

-

Browns Marina

Browns Marina -

Elizabeth on the Bay Marina

Elizabeth on the Bay Marina -

Blue Marlin Cove Resort & Marina

Blue Marlin Cove Resort & Marina -

Great Harbour Cay Marina

Great Harbour Cay Marina -

Romora Bay Resort and Marina

Romora Bay Resort and Marina

🇧🇿 BELIZE

🇧🇲 BERMUDA

🇧🇷 BRAZIL

Stella Marina

Stella Marina  Recife Marina

Recife Marina  Pier 26 Marina

Pier 26 Marina

Marina da Gloria

Marina da Gloria Marina da Gloria

Marina da Gloria Marina Bracuhy

Marina Bracuhy Marina Itacuruçá

Marina Itacuruçá Marina Itajaí

Marina Itajaí Marina Piratas

Marina Piratas

🇻🇬 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS

🇨🇻 CAPE VERDE

🇰🇾 CAYMAN ISLANDS

🇨🇱 CHILE

🇨🇴 COLOMBIA – Caribbean

-

Club Nautico Cartagena

Club Nautico Cartagena -

Club de Pesca Marina Cartagena

Club de Pesca Marina Cartagena -

Marina Puerto Velero

Marina Puerto Velero -

IGY Marina Santa Marta

IGY Marina Santa Marta  Manzanillo Marina Club

Manzanillo Marina Club

🇨🇷 COSTA RICA – Pacific Coast

🇨🇺 CUBA

🇩🇲 DOMINICA

🇩🇴 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

🇪🇨 ECUADOR

🇸🇻 EL SALVADOR

🇬🇮 GIBRALTAR

🇬🇩 GRENADA

🇬🇵 GUADELOUPE

🇬🇹 GUATEMALA – Pacific Coast

🇬🇹 GUATEMALA Rio Dulce

🇫🇯 FIJI

Copra Shed Marina

Copra Shed Marina Nawi Island Marina

Nawi Island Marina  Denarau Marina

Denarau Marina-

Musket Cove

Musket Cove  Royal Suva Yacht Club

Royal Suva Yacht Club Sau Bay Moorings

Sau Bay Moorings

🇭🇳 HONDURAS – Bay of Islands – Roatan

🇮🇹 ITALY

Marina dei Presidi

Marina dei Presidi  Marina di Balestrate

Marina di Balestrate Marina di Brindisi

Marina di Brindisi Marina di Cagliari

Marina di Cagliari Marina di Chiavari

Marina di Chiavari Marina di Forio

Marina di Forio  Marina di Teulada

Marina di Teulada -

Marina di Policoro

Marina di Policoro -

Marina di Vieste

Marina di Vieste -

Marina de Procida

Marina de Procida -

Marina de Villasimius

Marina de Villasimius -

Marina di Vieste

Marina di Vieste -

Marina Molo Vecchio

Marina Molo Vecchio  Marina Salina

Marina Salina  Venezia Certosa Marina

Venezia Certosa Marina

🇯🇲 JAMAICA

🇲🇶 MARTINQUE

🇲🇽 MEXICO – Caribbean

- Marina Makax – Isla Mujeres

- Marina Puerto Aventuras

- Marina V&V – Quintana Roo

- Marina El Cid – Cancún

🇲🇽 MEXICO – Pacific Coast

- ECV Marina – Ensenada BC

- IGY Marina Cabo San Lucas BCS

- Marina Palmira Topolobampo – SI

- Marina y Club de Yates Isla Cortes – SI

- Marina el Cid – Mazatlan – SI

- Marina Vallarta, Puerto Vallarta – JA

- Marina Puerto de La Navidad – Barra de Navidad – CL

- Marina Ixtapa, Ixtapa – GE

- La Marina Acapulco, Acapulco – GE

- Vicente’s Moorings, Acapulco – GE

- Marina Chiapas – CS

🇳🇿 NEW ZEALAND

🇳🇮 NICARAGUA – Pacific Coast

🇳🇺 NIUE

🇵🇦 PANAMA – Pacific Coast

🇵🇦 PANAMA – Caribbean

- Shelter Bay Marina

- Bocas Marina

- Solarte Marina

- Linton Bay Marina /a>

- Turtle Cay Marina

- IGY Red Frog Marina

🇵🇹 PORTUGAL

🇵🇷 PUERTO RICO

🇱🇨 SAINT LUCIA

🇸🇽 SINT MAARTEN

🇪🇸 SPAIN

Alcaidesa Marina

Alcaidesa Marina  IGY Málaga Marina

IGY Málaga Marina  Marina Del Odiel

Marina Del Odiel  Nautica Tarragona

Nautica Tarragona  Puerto Sotogrande

Puerto Sotogrande Yacht Port Cartagena

Yacht Port Cartagena

🇰🇳 ST KITTS & NEVIS

🇹🇳 TUNISIA

🇹🇴 TONGA

🇹🇨 TURCS AND CAICOS

🇻🇮 US VIRGIN ISLANDS

🇺🇸 USA – East Coast

- Safe Harbor – Marathon, FL

- Pier 66 Hotel & Marina – Ft. Lauderdale, FL

- Titusville Marina – FL

- Port 32 Marina Jacksonville – FL

- Oasis Marinas at Fernandina Harbor Marina – FL

- Morningstar Marinas Golden Isles St. Simons Isl. – GA

- Windmill Harbour Marina – Hilton Head , SC

- Coffee Bluff Marina – Savannah GA

- Hazzard Marine – Gerogetown, NC

- Holden Beach – Town Dock, NC

- Tideawater Yacht Marina, Portsmouth, VA

- Ocean Yacht Marina, Portsmouth, VA

- York River Yacht Haven – VA

- Yorktown Riverwalk Landing – VA

- Regatta Point Marina – Deltaville, VA

- Regent Point Marina – Topping, VA

🇺🇸 USA – Pacific Coast

🇻🇺 VANUATU

Primary Named Winds in the Mediterranean 🌬️BORA

| Wind Name | Direction | Temperature | Notes |

Bora |

NE | Cold & dry |

Katabatic wind, especially violent in N Adriatic; sudden gusts, winter stronger.

|

The Major Bora Wind Funnels Areas in the Adriatic

1. Southern Gulf of Trieste

2. Bay of Rijeka with the Kvarner Gulf

3. Coastline of Senj and the strait between Krk and Prvić

4. Velebit Channel between the eastern coast of Rab and Jablanac

5. Šibenik to Cape Ploča

6. Vrulje Bay between Omiš and Makarska

7. Northwest exit of the Mljetski Channel

The Bora is one of the most infamous winds in the Mediterranean — especially for sailors in the Adriatic Sea, and particularly along the coast of Croatia, Slovenia, and NE Italy. Here’s a breakdown of its effects on sailing:

🌬️ Bora Wind – Quick Facts

-

Direction: Blows from the northeast (NE) — offshore in most of the Adriatic.

-

Temperature: Cold and dry, especially in winter.

-

Origin: A katabatic wind, meaning it funnels down from high elevations (like the Dinaric Alps) and accelerates downhill toward the sea.

⛵ Effects on Sailing

✅ Advantages (if timed carefully):

-

Great downwind sailing from NE to SW if you’re headed south along the Adriatic.

-

Clear skies and visibility often accompany it once the wind stabilizes.

-

Flat seas may briefly appear at onset — before wave build-up begins.

⚠️ Risks & Challenges:

-

Sudden onset… the Bora can go from 5 knots to 45+ knots in minutes.

-

Gusts over 60 knots are not uncommon near Trieste, Senj, and Velebit Channel.

-

Dangerous crosswinds when sailing parallel to the coast, especially for boats exiting or entering harbors.

-

Short steep waves build up quickly in open water and become very uncomfortable and hazardous.

-

Anchor dragging is a common hazard; the wind can blow straight offshore and expose poor holding.

⚓ Strategy

-

Shelter on the lee side of islands or in well-protected harbors with NE protection.

-

Use Bora forecasts: many services (e.g., Croatia’s met service) provide alerts.

-

Secure anchorage with extra scope, especially in exposed NE-facing bays.

-

Avoid passages from Italy to Croatia (upwind slog ) during a strong Bora.

MUST SEE IN THE SEA OF CORTEZ 🇲🇽 MEXICO

Rock Paintings of the Sierra de San Francisco 🇲🇽

From c. 100 B.C. to A.D. 1300, the Sierra de San Francisco (in the El Vizcaino reserve, in Baja California) was home to a people who have now disappeared but who left one of the most outstanding collections of rock paintings in the world. They are remarkably well-preserved because of the dry climate and the inaccessibility of the site.

The central part of Baja California peninsula is a region of Mexico that concentrates one of the most extraordinary repertoires of rock art in the country, the Rock Paintings of the Sierra de San Francisco. The region is insular-like and kept the native peoples relatively isolated from continental influences, allowing the development of local cultural complex. One of the most significant features of the peninsular prehistory is the mass production of rock art since ancient times and the development of rock art tradition of the Great Murals.

The Sierra de San Francisco is the mountain range which concentrates the most spectacular and best preserved Great Mural sites, scale wise one of the largest prehistoric rock art sites in the world. Hundreds of rock shelters, and sometimes huge panels with hundreds and even thousands of brightly painted figures, are found in a good state of conservation. The style is essentially realistic and is dominated by depictions of human figures and marine and terrestrial fauna, designed in red, black, white and yellow, which illustrate the relationship between humans and their environment, and reveal a highly sophisticated culture. The paintings are found on both the walls and roofs of rock shelters in the sides of ravines that are difficult of access. Those in the San Francisco area are divided into four main groups – Guadalupe, Santa Teresa, San Gregorio and Cerritos. The most important sites are Cueva del Batequì, Cueva de la Navidad, Cerro de Santa Marta, Cueva de la Soledad, Cueva de las Flechas and Grutas del Brinco.

The landscape of the area is another significant attribute, understood as the extensive physical space in which, through rock art, the thoughts of their early dwellers, hunter-gatherers people who living here from the terminal Pleistocene (10,000 BP) until the arrival of Jesuit missionaries in the late seventeenth century, are expressed.North of San Ignacio lies a mountain wilderness, the deeply eroded remains of layer upon layer of volcanic outpourings. This rugged mass rises from the surrounding desert to heights of more than 5,000 feet and covers an area 35 miles from north to south and half of that from east to west. From its uplands, there are views west to Scammon’s Lagoon and the Vizcaíno Desert, northwest to the even taller Sierra de San Borja, and east to the abrupt eminences of Las Tres Vírgenes, taller and more recent volcanos that tower in front of the Gulf. The sierra embraces a world that would never be suspected from the low, barren lands outside. Groves of palms and pools of water are set between walls of vertical grandeur water-carved from rich-colored rock. A few ranches, built by rustic and hospitable people, nestle near the few water sources. Here also are the grandest reminders of the Painters, corridors decorated by their hands and haunted by their spirits.

Showing human figures and many animal species and illustrating the relationship between humans and their environment, the paintings reveal a highly sophisticated culture. Their composition and size, as well as the precision of the outlines and the variety of colors, but especially the number of sites, make this an impressive testimony to a unique artistic tradition.

ROCK ART ON A LARGE SCALE

The Rock Paintings of the Sierra de San Francisco encompass an area of 183, 956 ha, where more than 400 sites have been recorded, the most important of them within the reserve, near San Francisco and Mulege, over 250 in all. The inscribed property contains an exceptional repertoire of rock art that convey its Outstanding Universal Value. The sites have remained virtually intact and still have a good state of conservation. The integrity of rock painting sites and their surroundings has been maintained largely due to the situation of isolation and the low population density that prevails in the region.

Protection and management requirements

The Rock Paintings of the Sierra de San Francisco are protected by the 1972 Federal Law on Historic, Archaeological and Artistic Monuments and Zones and fall under the protective and research jurisdiction of National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). In addition, the property is entirely within the Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve; which grants it with additional protection. The Management Plan has been in operation since 1994 and has proved a successful strategy in the administration of cultural resources of the property. This model emphasizes the importance of defining the meaning of this heritage site, so that all management strategies are consistently directed toward the preservation of the values that make it important. Another key feature is the total involvement of all those groups that have an interest in the area under discussion. The Management Plan focuses on issues such as mitigation of the impact of visitors on sites and control and monitor of access. Some measures included the installation of reversible infrastructure in seven of the most visited rock painting sites and the definition of authorized access paths, the areas open to the public or restricted, and four levels of access for tourists. This system allows visitors to experience a wide range of sites and at the same time protects the majority of those who are very well preserved. In this sense the most popular sites have remained open under this Management Plan. Threats remain that have to be addressed, including those derived from the proposals to construct roads within the protected area which would jeopardize the existing integrity between the landscape and the rock art sites.

The medium and long term management expectations include obtaining additional legal protection through the presidential declaration of the area; allocating permanent custodian positions to improve monitoring, enhance the administrative and technological infrastructure of Sierra de San Francisco Information Unit located in San Ignacio town, capacity building for the custodians and guides and improvement of low-impact infrastructure for services.

more at https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/baja/great_mural_styles/index.php

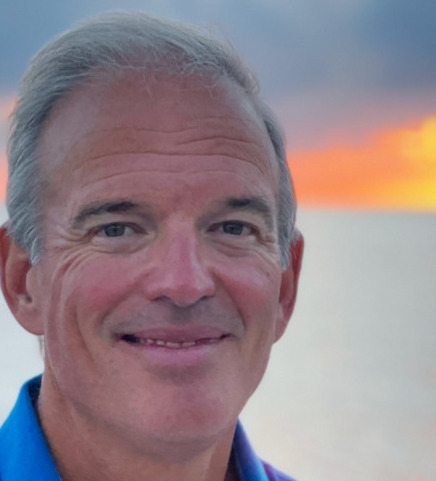

MEET THE FLEET  SY KNOT RIGHT

SY KNOT RIGHT

Walt & Jeariene

Current Location: Red Frog Marina, Bocas del Toro, Panamá

Vessel Name: SV Knot Right

Backstory: Walt’s daughters coined the name—claiming he’s “not right”—and the pun stuck. The name reflects both the humor and the freedom-loving spirit aboard.

A Call to the Sea

Both Walt and Jeariene were drawn to the cruising lifestyle through fond memories of earlier sailboat charters. For Jeariene, it’s the thrill of adventure and unknown horizons; for Walt, it’s about the sense of freedom that only open water can bring. What started as a pastime became a way of life, one that changes your perspective, with every calm stretch and every sudden squall.

“The sea teaches you quickly. One moment you’re sailing smooth, the next you’re in confused seas—it’s a mirror of our chaotic world,” Walt reflects.

Moments That Shift the Soul

They’ve both experienced defining moments offshore. For Walt, it was the surprise of shifting conditions that made him see just how unpredictable and raw the world can be. For Jeariene, the magic was quieter but no less powerful: watching dolphins swim beside the hull at night, lighting up the water with bio-luminescence.

“That glow reminded me, we’re caretakers of this planet. And we’d better not screw it up.”

Lessons Learned & Horizons Ahead

Living aboard Knot Right has brought its share of surprises. Walt laughs: “Everything on your boat is broken, you just haven’t found it yet.” The biggest lesson? Stay humble, stay alert, and keep moving forward.

The duo still has their eyes on the rest of the Caribbean, and their favorite destination is “TBD.” That’s the beauty of it, Knot Right isn’t just a name. It’s a reminder that sometimes the best course is the one not yet charted.

OP NOTE: Knot Right is part of the Original Gangsters and has been part of the Ocean Posse since the first Panama Posse t-shirt was printed back in 2017

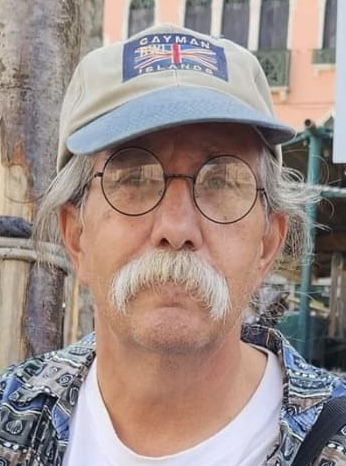

MEET THE FLEET  MV EPIC

MV EPIC

Marco & Karen

Current Location: PNW, Alaska.

Vessel Name: Epic

We were both born with an extra fin — or at least it feels that way. The sea has always called to us, and taking on the cruising life wasn’t so much a decision as it was an inevitability. It’s shaped how we see the world, stripped away the noise, and let us focus on what matters: the adventure, the simplicity, and the connection that comes from sharing it all together.

Right now, we’re sailing through the Pacific Northwest and Alaska — a place that still feels raw and untamed. But one of the most powerful moments we’ve ever experienced was much farther south, watching the sun sink into the horizon from the flybridge at Shroud Cay in the Exumas. That sunset — unhurried and immense — reminded us how small we are and how vast the world remains.

Cruising has taught us a lot, often the hard way. Like the time we were way off the beaten path and realized we didn’t have duck bills for the head. You learn quickly how the smallest things can turn into real problems out here. Still, the trade-off is worth it. We’ve crossed canals, rivers, and oceans, and every place has offered something: a lesson, a laugh, or a local who left an impression just by taking the time to connect. We try to do the same — to be present, to offer help, and to always say hello.

Our chart is far from full. Mexico, Panama, and maybe beyond — east, west, or south — all still lie ahead. So far, we’ve completed the Platinum Loop, navigated the Erie Canal, the Great Lakes, and the river systems three times. We’ve crossed the Gulf of Mexico, transited Lake Okeechobee, followed the Hudson River, and made our way through the Chambly, Richelieu, Saint Lawrence, Ottawa, Rideau, and Trent-Severn Canals. We’ve explored the Georgian Bay, North Channel, and the Bahamas. We’ve run the Inside Passage, the Gulf of Alaska, the Aleutian Chain, Semisopochnoi Island, False Pass, the Bering Sea, and the Pribilofs — even Dutch Harbor to Newport, Oregon.

And somehow, with all of that behind us, we still feel like we’re just getting started.

SOUTH PACIFIC POSSE – MEET THE CRUISING FLEET – SAT AUG 30 – NAWI ISLAND MARINA

-

15:00 YACHT MARKET OVERVIEW FOR BUYERS AND SELLERS PRESENTED BY

THE YACHT SALES CO -

15:30 THE PASSAGE TO NEW ZEALAND – PRESENTED BY OCEAN TACTICS

-

16:00 MEET AND MINGLE AND FREE RUM

-

17:00 LET THE FEAST BEGIN …

-

19:00 KAVA AND RUM AFTER HOURS

OFFICIAL OCEAN POSSE EVENTS

OCEAN POSSE KICK OFF 🇲🇽 BARRA DE NAVIDAD, MEXICO December 3-7 2025

MARINA PUERTO DE LA NAVIDAD, BARRA DE NAVIDAD, MEXICO

OCEAN POSSE & BEN TAYLOR STREET PARTY @ CANNES 🇫🇷 YACHTING FESTIVAL

TAQUERIA LUPITA, 72 Rue Meynadier, Cannes

GRAND PAVOIS 🇫🇷 La Rochelle – Sep. 24 2025

Gran Pavois La Rochelle, 20 Av. de la Capitainerie, 17000 La Rochelle, France

OCEAN POSSE 🇺🇸 SAN DIEGO BAY 4 DAY CRUISING SEMINARS SERIES @ SAFE HARBOR SOUTH BAY

SAFE HARBOR SOUTH BAY EVENT CENTER, CHULA VISTA, SAN DIEGO, CA

GRAND PAVOIS 🇫🇷 La Rochelle – Sep. 24 2025

Gran Pavois La Rochelle, 20 Av. de la Capitainerie, 17000 La Rochelle, France

GRAND PAVOIS 🇫🇷 La Rochelle – Sep. 24 2025

Gran Pavois La Rochelle, 20 Av. de la Capitainerie, 17000 La Rochelle, France

GRAND PAVOIS 🇫🇷 La Rochelle – Sep. 24 2025

Gran Pavois La Rochelle, 20 Av. de la Capitainerie, 17000 La Rochelle, France

GRAND PAVOIS 🇫🇷 La Rochelle – Sep. 24 2025

Gran Pavois La Rochelle, 20 Av. de la Capitainerie, 17000 La Rochelle, France

GRAND PAVOIS 🇫🇷 La Rochelle – Sep. 24 2025

Gran Pavois La Rochelle, 20 Av. de la Capitainerie, 17000 La Rochelle, France

INTRODUCING A NEW SPONSORSHIP AGENCY

NOUMEA YACHT SERVICES 🇫🇷 🇳🇨 NEW CALEDONIA – OUR SERVICES

We are pleased to offer a 10% discount on arrival and departure formalities for registered vessels this year.

- Arrival & Departure Formalities

We handle all formalities to ensure a seamless entry and exit from New Caledonian ports :

• Coordination with local authorities

• Pre-arrival preparation

• Immigration, customs, and biosecurity clearance

• Berth reservations

Special Offer : Enjoy a 10% discount this year exclusively for all South Pacific Posse participants. - Yacht Support & Technical Assistance

From quick fixes to full-scale refits, we’ve got you covered :

• Coordination of repairs and regular maintenance

• Access to a trusted network of skilled local technicians and suppliers

• Comprehensive refit services – minor upgrades to complete overhauls - Bunkering & Provisioning

We ensure your yacht stays stocked and fueled :

• Fuel arrangements, including duty-free fuel on departure

• Coordination with reliable bunkering facilities

• Provisioning of fresh food, beverages, spare parts, and more - Trip Organization & Land Logistics

We manage all logistics for your crew and guests :

• Car and van rentals, including chauffeured and VIP transfers

• Travel and accommodation arrangements

• Local SIM cards, entertainment bookings, and more - Entry Letters : I

n collaboration with immigration services, we provide entry letters for crew or guests arriving on a one-way flight to join your yacht - Tourist & Onshore Support

Enhance your New Caledonian experience with : - Our tailor-made itineraries

• Recommendations for anchorage, diving, sightseeing, and island excursions - Freight & Spare Parts

• Use our Noumea address as your local delivery point

• Assistance with customs-free clearance of spare parts - Yacht Keeping Agreement

Need to leave the territory for a while ? We take care of your yacht during your absence :

• Regular check-up visits

• Rapid response in case of any issue

• Coordination with service providers when needed

And much more !

Need something else ? Just ask, we’re here to help 😊

Clementine Givre

email: contact@nys.nc

tel: +687 79 56 01

DOWNLOAD THE NEW CALEDONIA RESOURCE MAP

Visit the nearby Jean-Marie Tjibaou Cultural Centre, Nouméa, New Caledonia

A striking fusion of modern architecture and Melanesian heritage, the Tjibaou Cultural Centre stands as a powerful tribute to Kanak identity. Designed by Renzo Piano, the centre’s soaring wooden structures evoke traditional “great houses,” yet are engineered with passive ventilation to withstand the South Pacific climate.

Inside, curated exhibitions, audio-visual displays, and a series of pavilions unfold the story of New Caledonia’s indigenous culture—from ancient myths and clan traditions to the political life of Jean-Marie Tjibaou, who championed cultural recognition and autonomy.

NEARBY

1. Îlot Amédée

A classic day trip from Nouméa, this small coral islet is home to a historic lighthouse and protected marine reserve. Its surrounding waters are famously clear, with excellent snorkeling—sea turtles, reef sharks, and a wide variety of tropical fish glide through shallow coral gardens.

2. Îlot Canard (Duck Island)

Just offshore from Anse Vata, this islet features an underwater snorkeling trail with informative buoys and healthy coral. It’s a quick hop by water taxi, popular for half-day excursions. Expect parrotfish, butterflyfish, and the occasional octopus beneath calm, shallow seas.

3. Signal Island & Îlot Larégnère

Both part of a marine park network, these islets lie slightly farther out but offer excellent reef exploration, beach walks, and a serene anchorage. Picnic tables and shaded huts invite a full-day visit. Snorkeling reveals eagle rays, clownfish, and soft coral fans.

4. Anse Vata Bay

Nouméa’s most famous beach is not only a hub for windsurfing and paddleboarding, but also offers decent snorkeling right off the beach. Its reef flats support schools of reef fish, and visibility is usually good in the mornings before the tradewinds pick up.

5. Baie des Citrons (Lemon Bay)

This protected crescent bay has easy entry points for swimmers and is often used by locals for snorkeling and night diving. The marine life includes pipefish, nudibranchs, and the occasional stingray. Cafés and palm-lined walks add to its urban charm.

OCEAN POSSE SPONSORS

OCEAN POSSE SPONSORS

- ABERNATHY – PANAMA

- BELIZE TOURISM BOARD

- BOAT HOW TO

- CABRALES BOAT YARD

- CENTENARIO CONSULTING – PANAMA CANAL

- CHRIS PARKER – MARINE WEATHER CENTER

- DELTA MIKE MARINE SUPPLY PANAMA

- DIGITAL YACHT

- DOWNWIND MARINE

- EL JOBO DIST. COSTA RICA

- FLOR DE CAÑA

- HAKIM MARINA AND BOAT YARD

- HERTZ RENTAL CARS MEXICO

- HOME DEPOT PRO MEXICO

- LATITUDES AND ATTITUDES

- MARINA PAPAGAYO

- NOVAMAR YACHT INSURANCE

- PANAMA YACHT BROKER

- PREDICT WIND

- SAFE HARBOR SOUTH BAY MARINA EVENT CENTER

- SAN DIEGO MARINE EXCHANGE

- SAFETY ONBOARD COSTA RICA

- SEVENSTAR YACHT TRANSPORT

- SHAFT SHARK

- SUN POWERED YACHTS

- WESTMARINE PRO

- YACHT AGENTS GALAPAGOS

OCEAN POSSE FLEET 🛰️ TRACKING

This page is designed to give interesting parties an overview. For specific vessel details including their floatplan, latest updates, changes, positions and specific location related questions please contact each vessel directly. Due to privacy we do not provide vessel contact information. You may track vessels via it’s own tracker or request AIS tracking from https://www.marinetraffic.com/ please note that this is also not accurate. There are many reasons why a vessel’s position is not updated and please do not conclude that a vessel has an emergency or is in need of assistance because it has not reported in lately. Sometimes they may just want to get away from it all and not tell you where they are. It is the responsibility of each vessel to file a float and check in plan and escalation procedures.

JOIN THE OCEAN POSSE

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MEET UP @ BOAT SHOWS AROUND THE WORLD | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SAVE MONEY, TIME AND REDUCE BOAT STRESS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Fun Fact about Panamanian Culture:

In Panama, the national dress — the “pollera” — isn’t just clothing, it’s an art form. A single hand-embroidered pollera can take over a year to make and cost up to $10,000. It’s worn during festivals and parades with pride, often passed down through generations, and paired with intricate gold jewelry and decorative hair combs called tembleques that shimmer as the wearer dances. It’s one of the most elaborate traditional dresses in the Americas.

PANAMA POSSE CANAL AGENTS

To arrange for transit with the Panama Canal Authority please contact our dedicated Panama Canal agents and sponsors of the Panama Posse and the Pacific Posse

CENTENARIO CONSULTING

Erick Gálvez

info@centenarioconsulting.com

www.centenarioconsulting.com

Cellphone +507 6676-1376

WhatsApp +507 6676-1376

Tidbits

Tidbits

- Dock Party

Thursday nights @ Red Frog Marina Bocas del Toro 🇵🇦

Petty Thefts Bocas del Toro

- PYTHIA 🦜Caleb I contacted the number a cruiser in the anchorage gave me as Aeronaval and someone else said was local police, but no answer yet. I called and texted both. I filed a report with CSSN. We’ll survive, it’s more an annoying violation than anything. I’m more than happy to buy from locals and hire them to do work, but it wasn’t enough this time. I’m sure that the thief watched us leave and took their shot. Second time I’ve been robbed on my boat now. And everything was locked. They just broke it.They stole almost nothing that will be useful to them since we immediately locked down the Kindles, tablet, and phone. He stole my brand new clothes and my swim trunks, leaving me with few clothes to wear myself now. It’s just dumb, he did damage and risked himself and barely got anything of value. He did more harm to us than good for himself. It will cost me thousands to replace what he stole that won’t do him any good.Pixel Buds Pro, Fire Tablet 8, Motor Power G phone, two Kindle Paper Whites (both that I have owned have been stolen now by different people in different places), two pairs of swim trunks, two button up shirts, two pairs of shorts one brand new, a towel, a fan, a mirror, a headlamp…all stuff he could carry in a canoe in a bag or pockets.We’ll be alright. More annoying than anything

DIDN’T GET YOUR INVITE TO BEZOS’ WEDDING?

Yeah… neither did Zuckerberg.

But his heli-on-deck toyship Wingman could’ve made the 450 nm hop to Venice without breaking a sweat.

One of our own, SY GARGOYLE II, caught the scene in Corfu

@ Garitsa Bay 39° 37.0833′ N 019° 55.6766′ E – and sent back proof:

“We’re rubbing shoulders with the zillionaire set here in Corfu today. Zuckerberg’s fleet is anchored nearby… but all eyes are on Opera — the 10th largest yacht in the world. Snagged a quick video scan for you.”

NOTE: In truth, these mega-yachts are often held in complex structured companies, making it tricky to pinpoint the precise owners of OPERA . But it’s undeniably an Al Nahyan family asset either Sheikh Abdullah or Sheikh Mansour who are high-ranking Abu Dhabi royals.

📍 Real sightings. Real stories. Just another day in the Ocean Posse.

Extraordinary Cruising °°° Join the Fleet

- Access vetted local knowledge, safety resources, and prior experiences to make your passage safer and more enjoyable.

- Unlock a Life of Adventure

Explore hidden destinations, experience new cultures, and discover the freedom of life at sea or near shore – on your terms. - Get VIP Perks & Discounts at marinas, chandleries and boatyards

Get exclusive discounts, priority access, and personalized support at partner marinas across the globe. - Observe the actions of Experienced Captains

Tap into a wealth of tips, tools, and real-world know-how from seasoned mariners to grow your skills and gain confidence. - Make Every Nautical Mile Memorable

Join events, meetups, and shared journeys that turn you voyages into unforgettable stories and lasting memories. - Cruise with a Conscience

Gain insights into sustainable practices and join a movement that protects the waters you love to explore.